TEACUP & SKULLCUP BOOK REVIEW

One day I searched ‘zen trungpa’ on the internet and the Amazon page for The Teacup and the Skullcup: Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche on Zen and Tantra came up first. So intriguing! I have been a zen student for a while and also read a majority of Chögyam Trungpa’s work. He has been my main ‘book’ teacher. The book was published in 2007. This is not so much a book review but rather a summary of what I discovered in connection with my own experience while reading it.

The material is drawn from two seminars that Trungpa Rinpoche led in 1974 in the US. It starts with an informing introduction by David Schneider where one learns about the close personal connections between Trungpa and the early American Zen teachers (Suzuki Roshi, Kobun Otogawa, Eido Roshi and Maezumi Roshi who founded ZCLA). At the time a lot of Zen students were drawn to Chögyam Trungpa’s teachings and he adopted a lot of zen practices in his dharma centers in the West, using zafus, working with the breath and performing kinhin. Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind was read at retreats, calligraphy and kyudo were practiced at Shambhala and Trungpa was also an ikebana artist and accomplished calligrapher (I recommend reading his writings on dharma art). Stories of Trungpa and his American Zen friends abound, involving drinking sometimes!

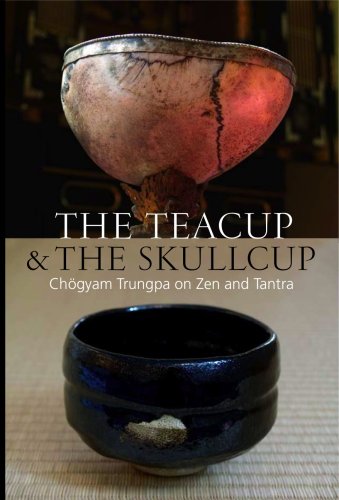

The lectures transcribed in the book distinguish between the Zen and Tantra traditions. This is illustrated in the title of the book or when he likens the Zen practioner to a beautifully dressed noble person and the Tantra practitioner to an unemployed unshaven samurai. In many ways unknown to me until now Zen somehow leads to Tantra because Zen according to Trungpa represents the highest mahayana achievement.

The book also features a translation of Faith in Mind (by HsinHsin Ming), a text read many times in Zen practice as some mantra antidote to the conditioned duality of the self. For Trungpa, Zen is the biggest cosmic joke ever played on humanity, a sort of straight jacket for the monkey mind. It’s true that in Zen, at the beginning one tends to feel very inadequate, the straight jacket being the precision and the simplicity of the discipline that eventually corners the egoself into making friend with itself. He doesn’t say straight-jacket, it’s a word that I personally find adequate and the conclusion that I draw from the book and my personal experience. In Zen, we learn about our own stupidity and self deceptions and this gives rise to prajna. He says: “The way Zen people seek prajna is extraodinarily precise”. It is true that the rhythm and constraints of Zen practice are very exacting. Discipline and clock work are part of the upaya. The lack of margin for error does squeeze the self juice quite properly. Trungpa also describes the meditation common ground between Zen and Tantra as a process of trapping the monkey by just sitting still: “Fundamentally, meditation is about training the mind without using any techniques”. Just as in ‘just sitting’.

Path distinctions between Zen and Tantra

Trungpa contrasts the two traditions by looking at their respective journeys. For him, in the Zen tradition of being here now still relates to a journey or a process while in vajrayana the notion of upaya is different, the upaya being vajrayana itself (the means and the method are the same as the realization itself – the journey stops being the goal). Tantric upaya approaches things more clearly in the sense that nothing is recorded in memory which avoids the problem of remembrance of experience, habit-forming thoughts which cloud reality (how many Zen students are derailed from their path by just experiencing kensho or some other opening experience then cligging to that!). The purpose of Tantra is to destroy the habitual memory bank so that you could see precisely without distortion (Memory is the beginning of duality – it is often stated that without memory the mind is nine times clearer). Also, while basic form (or formlessness) is the landmark of Zen, nowness is the landmark of tantra. No need to talk about saving others, it becomes automatic. The bodhisattva is no longer self-conscious of being a bodhisattva. Visualizations become a natural situation and not something that is superimposed on reality. Ordinary mind, the conclusion of Tantra. is wisdom born within (co-emergent wisdom).

The Yogacharan tradition in Zen and Tantra

In the lectures Trungpa connects Zen primarily to the yogacharan school of thought: believing in mind only. HsinHsin Ming’s Faith in Mind is a clear example of this approach. Only the integrity of the mind is being kept while everything else hangs quite loose in shunyata. He connects the Zen appreciation for art and aesthetic consciousness to Yogachara (“Often the discovery of shunyata is referred to in Zen as the treasure, the jewel, the gem. There is a sense of value, a sense of preciousness, that imitating the Buddha is very important”). Poetry and pretty pictures. In this world the shunyata experience is being spotted, noticed and recorded to memory. In Zen, one cannot just hang loose in shunyata: it has to be expressed and often turned into art. I get the sense that for Trungpa this is experience that is diluted, processed. Experience made into experience, making a trip out of it (as he often says, he was using ‘trip’ often, the time period being the psychedelic 70s). In the Vajrayana view this approach is too delicate, it has the potential for guts as he says. Yogacharan poetry is indirect while tantric poetry is more direct and gross. Although there is a yogacharan influence in tantra there is also something beyond: the ordinary mind. To quote directly from a talk: “[Tantra] is the fashion of the unemployed samurai, gruff and slightly grumpy” and “Instead of drinking out of beautifully molded tea cup you drink out of a skullcup” and finally “Instead of destroying the ego by poisoning it, by the message of shunyata or egolessness, you cut it in half in one big slash”. In other words, Zen is the skillful means of the straight-jacket for the egoself while Tantra is the razor sharp word that cuts through to clarity.

The Conclusion: Wild Zen, Crazy Tantra

Trungpa Rinpoche presents an interesting point of view, connecting mantras and koans. Mantra is the union of body and mind: speech binds mind and body together (Mantra means protecting the mind). It is first mind, acting as a simple receiver. Mantra is just an audio statement of things as they are; sounds with basic qualities within them that can only be experienced at the ordinary mind level thus bypassing conditionning. Trungpa compares koans to mantras. Like mantras, koans don’t make sense (koans only are translated in host languages while mantras are never translated, they are supposed to be in the language of the dakinis). Koans make one face one’s own stupidity, deception and facades. As opposed to mantra, koan practice inspires shunyata and prajna experience, there is a sense of going further/higher which is absent from Tantra. Mantras bring cosmic absorption, koans bring transcendent knowledge. The fun wildness (and humor!) of Zen is based on this transcendent knowledge while Tantra’s path is undiluted suchness… crazy wisdom, Padmasambhava is no Dogen Zenji!